Lutz Rathenow

The Fantastic Ordinary World of Lutz Rathenow:

Poems, Plays & Stories

Translated from the German by Boria Sax

& Imogen von Tannenberg

with an afterword by Boria Sax

Illustrations by Robyn

Johnson-Ross

& Boris Mukhametshin

ISBN 1-879-378-31-0 (paper)

176 pages, $15

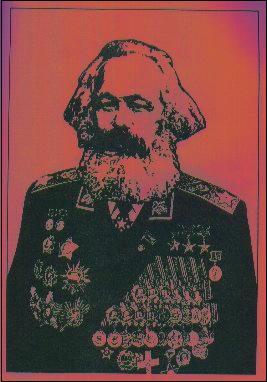

Anti-poster of Marx by Boris Mukhametshin

FROM THE PREFACE BY KARL AUGUST KVITKO:

"The world Berlin author Lutz Rathenow depicts is the colorless,

flat, thuddingly dull DDR — the

German Democratic Republic, as it called itself, or Communist East Germany,

as we knew it: a sub-Soviet, sub-standard, bureaucratic parody of a society

(1949-1990). And he depicts it very well, only not from the outside, with

detailed descriptions, historical costumes and polemical plots, but rather

from the inside, dropping in on the mind of one or another of its characters.

Here is the little man starved of human contact and longing for romance

('The Girl in Finland'), the timid bureaucrat standing in front of an office

door and wondering how to knock ('Mr. Breugel), the writer facing the blank

page and fearing both to write and not to write ('The Blank Page'). Here,

in other words, is Angst, paralysis, a funnel of doubt and indecision. Out

of it comes murderous resentment ('Professor Dr. Mitzenleim'), mocking defiance

('Reasons for Refusing to Make a Statement'), ironic futility ('Meditations

on Peace'). People who are emotionally starved, anxious and futile develop

a perverse sense of humor ('The Phone Call'); they find grim little pleasures

in their living death ('Obituary').

Rathenow's works crystallize not only a past, but also a present and recurring assault on the mind. The government, the political party, the church, the organization, the television program, the newspaper, the company, the office, the boss all want you to think the same way, their way, whatever the country and whatever the time. And if you do, this is what results: reduced capacity, distorted thought, fragmented language, inverted feelings, a sense of unreality, a drabness unto death. The Fantastic Ordinary World of Lutz Rathenow draws this lesson and thus the pleasure out of the painful republic."

Artwork from the book cover by Robyn

Johnson-Ross

Excerpt from the book:

No

Ordinary Spy

translated by Boria Sax

The spy this story is about was no ordinary spy. He was the best in

the land. He cleaned his ears five times a day and could write down three

conversations at once. At a distance of seven hundred meters he could hear

when somebody coughed against the wind or simply muttered a curse to himself.

With his exceptional hearing he could ascertain whether one lit a fire with

the daily newspaper taken straight from the mailbox, without having first

studied it with appropriate thoroughness.

When this spy crept soundlessly through the streets, nobody saw him, at

least not in his normal form, something he hardly knew himself. He changed

his name and appearance several times a day. At first he imitated street

sweepers, moody greybeards, cripples, nursery-school teachers, undertakers;

later he transformed himself into objects, disguised himself as a wastepaper

basket, park bench or shrub in order to follow a conversation unnoticed.

He gradually perfected his ability to continue for hours as an object. Even

accidental steps or dogs relieving themselves did not make him lose his

composure. Once, it is true, he resisted being carried away by two men who

were stupified as what they presumed to be a piece of junk, the exact nature

of which they intended to determine, bodied forth as a person and hurried

away without giving them a second look.

In the main, he performed his duties without complications. The Ruler so

valued his reports that he was regularly admitted into the presence of the

highest officials in the land. Naturally under cover of the greatest secrecy;

even the ministers were said to have plans other than what they gave out.

Thus by dint of his talent the spy was placed only in the most exclusive

circles and assigned by the Ruler to check out primarily the Chief of the

Secret Police. This was, after all, a democracy, everyone had to be kept

track of. His immediate superior, the Chief of the Secret Police, on the

other hand, ordered that his first concern should be to observe the behavior

of the Ruler: democracy means that nobody is exempted from observation.

Unfortunately, the spy could not savor this uncommonly ticklish situation

in all its piquancy. His increasingly refined ability to conceal himself

in enclosed spaces hindered complete fulfillment of his assigned tasks.

By now he no longer spoke, was barely able to whisper, audibly enter an

office or, indeed, face someone else as a human being. He continued on as

a piece of furniture in the room. People sat on him, left plates, pressed

out cigarettes.

In the beginning, he deposited plain-text reports in the offices of his

superiors and picked up new instructions left for him; that was when the

floorboards in the hallway creaked more loudly than usual, indicating his

change of position.

But later, after he had several times been decorated with the "Golden Ear,"

the sleuth used codes specially contrived to prevent possible contamination.

Ultimately he renounced writing altogether and tapped out the information

on microfilm that he hid at varying locations, so that only by chance could

the Ruler and the Chief of the Secret Police obtain the data, which was

barely decipherable in any case. The spy did his recherche conscientiously,

by this time no longer nervous, though he remained motionless for weeks

on end as a folding chair in the room of the executive and reflected upon

a method of delivering reports that would be absolutely foolproof, by which

he would need neither to speak, to write or even to move. Something like

thought transference, an idea that eventually failed due to the insufficiently

conspiratorial mentality of his taskmasters.

The Ruler and the Chief of the Secret Police forgot the existence of their

most capable informant and let an entry be placed in his file: missing,

presumably killed in a street fight. There was no time to go over the matter.

The state leaders were set upon and toppled by an ever increasing number

of demonstrating people.

Now the happy ending: good times began without a Secret Police and a Ruler

who both had to fear losing power. The spy, however, finding that an insufficient

need for denunciations deprived his activity of meaning and therefore his

real motivation to discover ever more elaborately contrived methods of disguise,

this spy gradually degenerated into a man who realized that he had become

superfluous.

He joined a vaudeville show and demonstrated to an astonished public how

one turns into a table or hat rack. But loud applause did not prevent his

performances from becoming progressively joyless. One day he refused to

present himself to the public as a curiosity.

He still retained his considerable ability in hearing and smelling, and

was able to work in a clinic. After acquiring a certain routine, he could

diagnose a stomach ailment simply on the basis of how the mouth smelled.

In addition he was assigned to listen to the chests of all the patients

to see if there was an irregular noise. For that he needed only his ears.

It goes without saying that he performed his duties exactly.